Cinema Sunday (11/27/11)

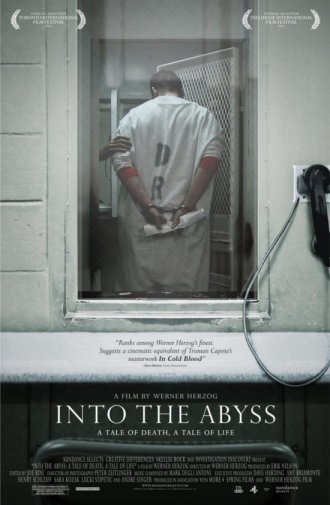

Of all my beliefs, my across-the-board opposition to the death penalty is the one I not only have difficulty explaining to others, it’s the one I often have trouble justifying to myself. In his new documentary, Werner Herzog turns his shrewd and perceptive eye toward one particular case in Texas (which, as we all know, is the McDonald’s of capital punishment), that of Michael Perry and Jason Burkett, who were convicted of the murder of three people in 2001: Sandra Stotler, her son Adam, and his friend, Jeremy Richardson. Perry received the death penalty; Burkett, a life sentence. The movie weaves together interviews with Perry (conducted eight days before his execution) and Burkett, as well as family members, police, and citizens of Conroe, Texas. It’s a horrifying, fascinating look at the human cost of capital punishment that is effective precisely for what Herzog chooses not to say.

The movie has been branded (not by Herzog) as a documentary ostensibly about the death penalty, but as I watched it, all I could think is that it’s really a movie about loss. Every last person in the movie has been indelibly and profoundly touched by it. There’s the policeman who walks Herzog through the crime, and the victims’ daughter and sister who acknowledges that the death penalty isn’t very Christian, but, hey, “some people just don’t deserve to live.” There’s the woman at a local bar who was very nearly Perry and Burkett’s victim and the former Texas death house guard who walked away from his job and gave up his pension because he was finally sickened by what he was asked to do on a regular basis. And, yes, there are the murderers themselves, both of whom had the deck stacked against them from a very early age. You see this loss in their eyes – how they can never quite meet the camera’s gaze head-on – and in their voices, which often tremble with emotion, ten years after the fact. Herzog himself has said that Into the Abyss isn’t a movie about capital punishment, and I think he’s right. It’s a movie about the many permutations of loss, and how this one particular case refracts its different facets like light bouncing off a diamond.

One of the most remarkable things about Into the Abyss is how even-handed it is. Herzog is always a powerful presence in his documentaries – paradoxically so, given his unassuming demeanor and soft-spoken, heavily-accented voice – but even though he says early on that he opposes the death penalty, we never get the feeling that he’s pushing an agenda here. The most direct he ever gets with a subject is when he suggests to the Stotlers’ daughter and sister that capital punishment doesn’t seem very Christian. In fact, by showing us grisly crime scene video from 2001, Herzog doesn’t shy away from the brutality of Perry and Burkett’s crime, so, in a way, we’re even less predisposed to feel sympathy for the two men. But, as with all of Herzog’s documentaries, the interviews tell the real story. And the most powerful story they tell – to me, at least – is that capital punishment is staggeringly wrong.

Here’s how it works for me, in the context of the movie. There can be no doubt that in a vast majority of death penalty cases (let’s say 99%) the perpetrator had a clear and distinct choice not to commit the crime. We see that in Perry and Burkett’s case. The murder of Sandra Stotler was the very definition of a senseless crime: she was killed for her car. And the murders of Adam Stotler and Jeremy Richardson were perhaps even more senseless, occurring after Perry and Burkett had disposed of Sandra’s body. These two men very clearly had the choice not to what they did, but they did it anyway. Their guilt, even though both men protest their innocence, isn’t an issue for me, and I don’t think it is for Herzog either. Based on the facts the movie presents us with, I don’t think there’s any question that Perry and Burkett murdered Sandra and Adam Stotler and Jeremy Richardson, and they very definitely had the choice not to commit the murder.

But the question then becomes, do they deserve to die for it? And here’s where the movie helped me clarify my own thinking on the issue. What the proponents of the death penalty fail to realize is that none of these crimes happen in a vacuum. It’s not as though Perry and Burkett were college-bound, straight A students who just one day decided to kill a woman for her car. I would argue that their pasts significantly contributed to the crime they would eventually commit. The most compelling evidence of this comes from Burkett’s father, himself a multiple felon who was in jail serving a thirty-year sentence at the time of his interview. He admits that he was a horrible father who was never around for Jason because he was in and out of jail during his son’s childhood, and he also says that he feels a tremendous amount of guilt for Jason ending up where he did. We don’t learn much about Perry prior to the murders, but we do know he was a homeless 17-year-old at the time he met Burkett. How can we not look at this information as a mitigating factor in their crimes?

I’m not in any way attempting to absolve them of their guilt or trying to make the case that they didn’t deserve punishment. I’m simply trying to make sense of why it’s acceptable to execute two men who very likely had their decision-making facilities diminished by their poor childhoods. How, after learning all we do about Burkett’s childhood, can we in any way believe he was capable of making intelligent – even moral – choices? But maybe that’s the point. Burkett’s father was allowed to come to court, explain his son’s childhood, and plead for Jason’s life. Burkett didn’t receive the death penalty; Perry did. But was Perry, a homeless juvenile, any less damaged? His own father died in prison days before Perry’s interview with Herzog. Are we to believe that because Perry was executed he was capable of making a choice Burkett was not?

It feels to me that when someone’s life is on the line – even the life of a convicted felon – we shouldn’t be haggling over inconsistencies. We shouldn’t allow someone to die because he couldn’t afford the right lawyer. We shouldn’t be willing to accept the statistics that say minorities are more likely to receive the death penalty than white convicts. We shouldn’t buy into the fallacious argument that capital punishment somehow acts as a deterrent to future crime. How is a life sentence without the possibility of parole somehow less satisfying as a punishment than the death penalty? In both cases, the convict’s life has been taken from him, except in the case of the life sentence we’re not condoning state-sanctioned murder.

And, finally, that’s what I I keep coming back to: the death house guard who quit his job rather than assist in the taking of another life. Either murder is right, or it isn’t. This equivocation we’re doing as a society – deciding that some people deserve to live and others don’t – strikes me as both dangerous and at odds with the values this country is supposed to (but often fails to) represent.

I often wonder, though, how my view of capital punishment would change if someone I loved were taken from me. Would I be as steadfast in my belief that it’s wrong, or would I, like Sandra Stotler’s daughter, be consumed with a desire for revenge? The most honest answer I can give is that I hope I never have to find out.

*****

Current listening:

Caithlin de Marrais – Red Coats (2011)

Current reading:

Guillermo del Toro and Chuck Hogan – The Strain (2009)

Last movie seen:

The Muppets (2011; James Bobin, dir.)

Posted on November 27, 2011, in movies, pop culture and tagged capital punishment, Cinema Sunday, death penalty, movies, Werner Herzog. Bookmark the permalink. 2 Comments.

Second review of this movie I’ve read this week. Both very positive. The film seems a lot like a modern reworking of The Thin Blue Line. I’m an admirer of Herzog’s work, particularly his documentaries, so will have to give it a look. Absolutely love your line about Texas being the McDonald’s of Capital Punishment.

It’s a great documentary; one of Herzog’s best, I think. It’s pretty amazing how he’s able to continually surprise after so many movies. Thanks for checking in.