Blog Archives

Partners in Crime

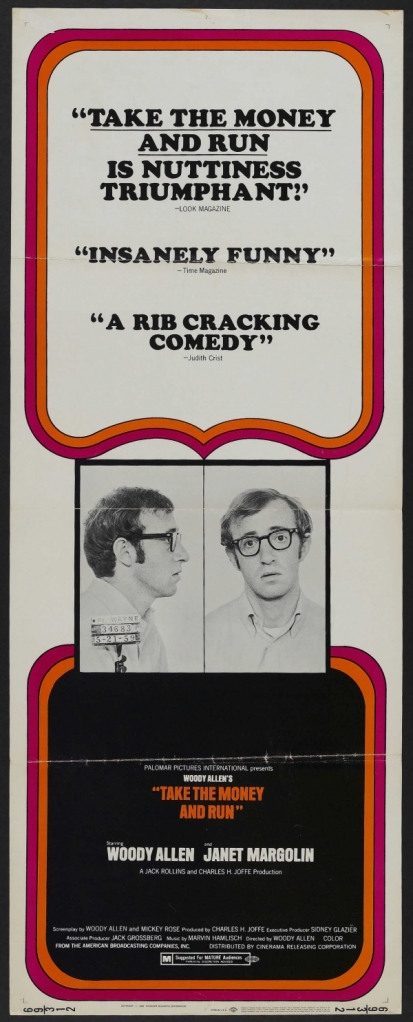

Eons ago (aka May), I set myself the ambitious task of watching and reviewing all 41 of Woody Allen’s feature directing credits. I made it through exactly one movie (his first, 1966’s What’s Up, Tiger Lily?) before I predictably got bored with blogging altogether and found other ways to waste my time. But now that I’m back and trying to take this more seriously (and in defiance of the kind of movies I’m supposed to be watching a couple days before Halloween) I took a look at Allen’s second film – and his first conventional writing/directing job – 1969’s Take the Money and Run. It was second time watching the movie, but the first time in probably fifteen years.

Eons ago (aka May), I set myself the ambitious task of watching and reviewing all 41 of Woody Allen’s feature directing credits. I made it through exactly one movie (his first, 1966’s What’s Up, Tiger Lily?) before I predictably got bored with blogging altogether and found other ways to waste my time. But now that I’m back and trying to take this more seriously (and in defiance of the kind of movies I’m supposed to be watching a couple days before Halloween) I took a look at Allen’s second film – and his first conventional writing/directing job – 1969’s Take the Money and Run. It was second time watching the movie, but the first time in probably fifteen years.

The first thing I noticed – within the first couple minutes, in fact – is how sublimely silly it is. Given the urbanity (and, let’s face it, increasing humorlessness) of Allen’s later films, it’s easy to forget just how funny his earliest movies are. The jokes are often broad and come in rapid fire succession – in fact, you can draw a straight line from Take the Money and Run (as well as several other films from Allen’s early filmography) to Airplane! and the Naked Gun films, as well as Mel Brooks’ Blazing Saddles. For those who only know Allen from his late 70’s masterpieces Annie Hall and Manhattan or recent films like Match Point and Midnight in Paris, it will be something of a revelation to watch the extremely funny running gag where various figures throughout Allen’s character’s life (a neighborhood bully, a truck driver, a courtroom judge, Allen himself) take off his glasses and step on them.

The movie is shot mockumentary-style, and the plot – such as it is – focuses on petty thief Virgil Starkwell (Allen) and his many run-ins with the law. We get a little backstory, meet Starkwell’s parents (who wear Groucho glasses, nose, and moustache throughout the movie to protect their identity – one of the jokes that hasn’t aged especially well), and then spend the rest of the movie watching as Starkwell commits crimes, falls in love with the beautiful Louise (Janet Margolin), and bounces in and out of jail.

It doesn’t sound particularly funny in print, but the gags are clearly the engine that drives this vehicle, so the plot is secondary to watching Allen throw a bunch of jokes at the wall and seeing what sticks. And, to be honest, not everything works, which is only to be expected of a 40-year-old comedy. (I’m reminded of the David Berman poem where the narrator argues that anyone who laughs at Shakespeare’s comedies is clearly trying too hard.) There’s the previously-mentioned disguise for Starkwell’s parents, and there’s a too-long sequence early in the movie where we see Starkwell try (and fail) to play the cello in a marching band.

The broadness of the jokes is the problem (although I love the line from the cello teacher about Virgil blowing into the instrument), but I don’t see this as Allen’s fault as much as it’s simply an unfortunate characteristic of many comedies of the same time period. I remember joking with my college roommates about how so many comedies of the late 60’s and early 70’s got resolved by having a pie fight or a go-kart race (or, better yet, a pie fight during a go-kart race), and a few of the jokes in Take the Money and Run follow that formula: broad and wacky because that’s just what you did.

Allen would go on to fine-tune this tendency in his next few movies (especially Bananas, Sleeper, and Love and Death), and we see signs of this maturity even here, along with his love of language and wordplay. One of the very best scenes in the movie hinges on Allen’s poor handwriting as he attempts to hold up a bank:

The crux of the joke is a small one (the difference between gub and gun and apt and act), but the earnestness of the characters – apparently unaware that they’re in a broad comedy – is what pulls it off. Virgil is dead-set on convincing the bank employees that his handwriting is perfectly legible, and the employees are so by-the-book that they won’t consent to being robbed until this little technicality is resolved. And of course this is played against the inherent ridiculousness of the scene – that the employees would take Allen’s note completely seriously and argue its legibility.

The movie is full of small, delightful moments like this one, where the reality of the situation is placed in counterpoint to the obliviousness of a key character. There’s a scene late in the movie where Virgil and the other members of his chain gang have escaped custody but failed to remove their shackles. They take shelter at an elderly woman’s house, and when the local law comes calling, they manage to trick the policeman by claiming they’re the old woman’s family, standing in a clump, and shuffling as a group whenever they have to move. The cop doesn’t see their chains, and it’s the sheer unreality of the scene that gives it its kick. It’s funny precisely because it’s so stupid, which, as is typical of Allen, is a highly intelligent move to make.

Take the Money and Run isn’t Woody Allen at his best. But it is Allen learning how to play his instrument, and it’s surprising to see just how quickly he would become a virtuoso. In the next decade he would direct seven more movies, including three revolutionary comedies in the same vein as Take the Money, a Best Picture Oscar winner (Annie Hall), and my all-time favorite movie (Manhattan), which manages to be both hysterically funny and emotionally devastating. Take the Money and Run isn’t perfect, but as calling cards go, it’s a hell of a thing.

My other Woody Allen reviews:

5/2/11: What’s Up, Tiger Lily? (1966)

*****

Current listening:

Mercury Rev – Deserter’s Songs (1998)

Current reading:

Alan Warner – Morvern Callar (1995)